Hello! Even though it’s officially autumn on the calendar, we’re still experiencing some hot days. As the saying goes, “The heat and cold last until Higan.” I’m hopeful that temperatures will start to drop soon.

Right now, Japan is in the season of Higan. Higan occurs twice a year, in spring and autumn, encompassing three days before and after the equinoxes. During this time, it’s customary to honor our ancestors, often by visiting graves or offering food at family altars.

A traditional sweet enjoyed during Higan is called “ohagi.” Today, I’d like to talk about ohagi.

What is ohagi?

Ohagi is made from a mixture of mochi rice and regular rice that’s cooked together. Unlike mochi, the rice is not fully pounded into a paste; instead, it’s lightly pounded so that some grains remain intact. The rice is then shaped into balls and coated with sweet red bean paste, soybean flour (kinako), or sesame.

When you eat it, you can savor the sweetness and aroma of the coating, along with the soft texture and slight chewiness of the rice, making it a beloved traditional sweet.

there are alternative names for ohagi?

Ohagi is a staple during the autumn Higan. Interestingly, it’s the same confection as “botamochi,” which is eaten during the spring Higan.

There are various theories about the naming. One prominent theory comes from the 18th-century encyclopedia Wakan Sansai Zue, which states that botamochi is named after the peony flower (botan), a spring flower; while ohagi is named after the bush clover (hagi) that blooms in autumn. However, in some regions, there are distinctions based on the type of red bean paste used: “koshian” (smooth) for botamochi and “tsubuan” (chunky) for ohagi, or vice versa.

The custom of eating botamochi and ohagi during Higan is thought to be part of ancestor worship and a way to offer thanks for the harvest in autumn and to pray for a good yield in spring.

What about summer and winter names for ohagi?

Ohagi also has different names in summer and winter! In summer, it’s called “yobune,” and in winter, “kitamado.”

Why these names?

Unlike mochi, ohagi doesn’t involve pounding with a pestle, so there’s no sound of “pounding.” After cooking the rice, we just lightly crush the rice with the pestle.

Since there’s no pounding sound, neighbors might not know when it was made. This led to the term “tsuki(arrival) shirazu” (not knowing when), transforming into “yobune” because one wouldn’t know when a boat arrives at night.

As for “kitamado,” it follows a similar logic: since there’s no pounding sound, people might not know when it was made. The change here is in the kanji. “Tsuki shirazu” becomes “tsuki(moon) shirazu” (not knowing when it’s moonlit), referring to the moon not being visible from a north-facing window, hence “kitamado.”

These names are quite clever and interesting. A wonderful play on words!

In the past, it wasn’t something you bought.

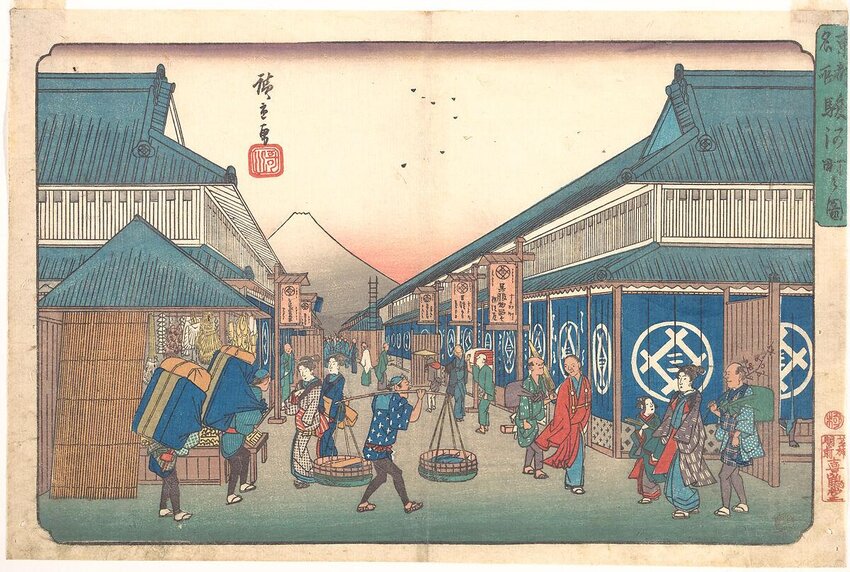

During the Edo period, it was customary to gift homemade ohagi during Higan. As sugar production increased in Japan, ohagi became more accessible, allowing families to make it at home.

People would exchange homemade ohagi with neighbors during Higan, as noted in the late Edo period book Morisada Mankō (1853).

Just as Oda Nobunaga received candy from Portuguese missionaries, sweet confections have long played a role in strengthening relationships between people. Ohagi had a similar role in fostering connections with neighbors.

Edo period was a time of development for wagashi.

While families used relatively inexpensive brown sugar, there were also famous shops in Edo selling ohagi made with white sugar, which thrived during this time.

The late Edo period saw the domestic production of sugar leading to the development of popular wagashi. By this time, shops were already selling three types of ohagi—red bean paste, soybean flour, and sesame—similar to what we see today. The culture of regularly buying and enjoying wagashi has been well-established among the common people!

The evolution of ohagi.

Ohagi, a traditional wagashi, may seem simple, but it has evolved into more stylish and modern variations.

Oh! huggy!!

https://oh-huggy.com/

Mori no ohagi

https://morinoohagi.jimdofree.com/

Takeno to ohagi

https://www.takenotoohagi.com/#/

It’s amazing to see how much depth there is to just one type of wagashi, indicating that there’s still room for innovation in the world of Japanese sweets.

What do you think? This time, I discussed ohagi. I wanted to share more about the atmosphere in wagashi shops during Higan, but I’ll save that for another occasion since it might take a while to explain.

Thank you for reading! I look forward to seeing you at the next post!